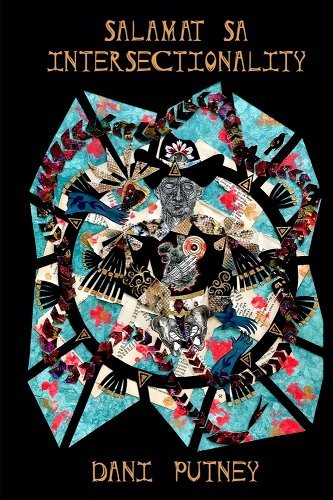

Dani Putney on liminality, pop culture, and the West in their new collection Salamat Sa Intersectionality

We interviewed Dani Putney, a contributor to our Winter 2020 issue.

Dani Putney is a queer, non-binary, mixed-race Filipinx, and neurodivergent writer originally from Sacramento, California. Their poems appear in outlets such as Empty Mirror, Ghost City Review, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Juke Joint Magazine, & trampset, among others, while their personal essays can be found in journals such as Cold Mountain Review & Glassworks Magazine, among others. They received their MFA in Creative Writing from Mississippi University for Women & are presently an English PhD student at Oklahoma State University. While not always (physically) there, they permanently reside in the middle of the Nevada desert.

You can visit their website at https://daniputney.com/ and purchase their book Salamat Sa Intersectionality here: https://okaydonkeymag.bigcartel.com/product/salamat-sa-intersectionality.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Winona Rachel: I’m currently in a prosody class right now, and we’ve been talking a lot about the relationship between form to content and the sort of tension that can emerge, along with the the possibilities for subversion, reinvention, and inversion. So I guess I was just curious sort of how you see your relationship to form as a poet?

Dani Putney: Yeah, that’s a great question. In general, I write free verse, but it’s not free verse in the sense that I’m writing without any rules. It’s just that the rules are made up in my head. I have a few contemporary sonnets in my poetry collection, namely “Call Me Wallaby” and the “Nevada” poem, and in the first section I wanted to have a kind of Petrarchan turn. If you’re familiar with Petrarchan sonnets, they have the octave at the beginning, the first eight lines and then a sort of volta moment, a turn, and then a sestet. And I really wanted that kind of form to be represented in those poems. But besides, like you know specific forms like sonnets, I generally think about how I can manipulate white space and how that provides its own sort of content, whether through silence or through, you know, caesuras that maybe unsettle the reader a bit. And there’s a few of those caesuras, not a few but a lot of those caesuras in my collection, especially in poems like “To Judith Butler” where I’m thinking about expanding gender and my own unravelling identity, so I want to have those caesuras represent that expansion, that kind of dilation of what’s happening.

So even if it’s not completely evident on the page, or if you don’t talk to me personally, there’s always some sort of formal guidance that I’m following in my head that I’m bringing on to the page.

WR: Very cool. As sort of a follow up to that, I was particularly struck by some of these juxtapositions of everyday, uncensored language and content with a sort of elevated, academic or literary voice. One example I found of this was in “Dear Jeremy” where there’s this—what I presume is a reference to Renaissance ideals of beauty and Italian painters alongside phrases such as “I sucked your dick.” I guess I wanted to hear a bit more about your choices to juxtapose those two different sorts of paradigms with each other.

DP: Yeah I love that you caught that, because that’s something I very intentionally do in most of my work. I feel that my “register” of language, like my parlance if you will, is a natural fusion of those elements, so I feel like when I’m speaking or, you know, writing poetry, I want to represent all the facets of my life and my identity if possible. And that includes the highbrow academic language, which I’m trained in and I’m versed in, but also I’ll say “I sucked your dick” or swear, or I’ll have a sailor’s tongue and that’ll just naturally come up. It even comes up in class or when I’m teaching students, right? I’ll just say these things, and I think students generally respond well to it. Just my natural sort of diction.

I think my poetry is a great way to manipulate that and exploit that, but also even more than that, it’s a great way to push it further. Maybe in ways that I might not bring up. Like with that poem “Dear Jeremy” I probably wouldn’t just phrase it to some rando “I sucked his dick.” You know, I’m not probably going to say that unless you’re my friend, but the fact that I can bring this up and juxtapose it with this Renaissance-esque language, especially because it appears close to the poem “Michelangelo” which is directly related to Michelangelo’s art. So I feel like it’s a perfect way for me to subvert that.

But also on an abstract plane, you guys are probably familiar with the term liminality, but I always think about liminal spaces and I’m a very liminal person myself being nonbinary, especially a male-bodied nonbinary person, and that wasn’t even something I felt like I could be. Like, growing up I always saw female-bodied nonbinary people and I was like oh I feel different. Not like a man. But I guess I can’t be nonbinary, because there’s nobody like me, right? But then, of course, I started to come into my identity, I started to accept it and express it more outwardly and I was like no, I can be whoever the fuck I want to be. So for me having that highbrow of more “pedestrian” language is kind of me saying this is my unique diction, my unique voice, and I can say whatever the fuck I want to say, and that’s totally chill and totally me. I’m always kind of inhabiting this in-between space and I feel like having this diction that isn’t completely sophisticated but isn’t completely a sailor’s tongue is kind of who I am as a poet and as a person.

WR: Yeah. Not to belabor the point of form, but I had one other thing that interested me which was in the “The High School Spelunker’s Guidebook,” which is kind of divided into two halves, Verso and Recto. I think these titles refer to the front and back sides of a printed page, and I was sort of interested in this form with a hinge in the middle and this change from we to I, but then also the repeated words and the subversion of the same phrases in each of the halves. So I guess I was just curious how that poem evolved and whether you started writing into this idea or whether it emerged more organically.

DP: Yeah that’s a great question. I love that poem because it’s something that I’ve been working on for a while and the published version with the Verso and the Recto, that’s kind of the ideal version that I wanted. I always kind of envisioned this form to begin with, which isn’t something I usually do. I usually highlight the content with the form, but I wanted to have this spread, like the book that’s in the title. But because of publishing restraints and the way that it might appear online, I couldn’t really have that spread and so it appeared in kind of like a two-page form. Then I tried to do it in maybe two pages but one is on the left and one is one the right. Then I was talking to my publisher, Okay Donkey, and was like can I have this on a verso and a recto and they were like “We can make that happen.” So this book is like the perfect culmination of what I originally wanted this poem to be, to have that kind of dialogue across the spread and then to have that silence in the middle, that big break. Like, the spine of the book. And I think that silence is really important to the turn that happens. And I’ve been talking about sonnets—that is kind of like a volta for me in the book. Like, using the typographic elements of the book itself. That is a big volta where it turns from the we to the I, and the I is being betrayed by the other person in the “we.” I really wanted that big break to happen, and the only way that I could see that really happening on the page was using a spread with verso and recto. I’m really glad that you noticed that, because that’s probably one of my favorite formal—or more formal—poems that I’ve written, and I’m definitely glad that my publisher was really excited to do that in the book.

WR: Yeah that was definitely one of my favorite poems in the collection. So my next question pertains to the title—I looked it up and “salamat sa” means “thank you for” in Tagalog, correct? Which makes the title of your collection “Thank You for Intersectionality.” It seems like a lot of your poems grapple with identity, intersectionality, and liminality. I guess I was wondering if you explain a little more about how you came up with this title.

DP: Yeah. I’m really proud of the title, it’s one of things I’m most proud of about the book. It didn’t actually come to me until quite late in the process, but I had actually written that poem in the book way before I came up with the title. But I was soul-searching for the title, thinking of words or phrases in the book or even a title itself from a poem that could best represent what I was doing and then I was like oh I’ve already written it. “Salamat Sa Intersectionality,” totally the perfect title and also because a lot of what I’ve been doing in other work that’s outside of the book is trying to reclaim my Filipinx heritage. I’m mixed race myself, my mom was a picture bride from the Philippines and I have this really complicated colonialist history through my white father being in the military and being part of the militarization of the Philippines—he was actually stationed there. But then also, speaking of my mom’s positionality in that, and also how we were basically forbidden from learning to speak Tagalog growing up, which is one of my mom’s languages. She also speaks Cebuano, which is a language that’s from a particular region of the Philippines called the Visayas.

But yeah, I wanted to have this title—selfishly—in that reason to reclaim my Filipinx identity and assert myself as somebody who is allowed to be Asian-American, is allowed to exist in this space. Because a lot of my personal struggle and insecurity you might see on the page is not feeling Filipinx and not feeling Asian enough because I’m this sort of mongrel, you know. Not Asian but not white, in between. I have relatives from across the globe but then I have this colonialist history that I have to deal with, the murder and rape of Filipinas, that complicated history. But then on top of that, there’s the Spanish colonization too. And that’s a little bit not what you asked for, but that’s part of the reason why Spanish words appear in the collection too because of the Philippines’s long-standing Spanish colonial period. It was, I believe, over 300 years before the United States took control of the Philippines for about a 50-year period. So yeah, for me with Salamat Sa Intersectionality, that really kind of marries all of those different elements into one succinct, three-word title while also allowing me to kind of reclaim an identity that I feel like I’ve always been kind of proximal to but I haven’t been able to assert myself in. And so this book, this title, is sort of like a way for me to say hey this is me. I’m queer, non-binary, Filipinx, neurodivergent, I’m all of these things and I’m beautiful and I’m a kaleidoscope and I’m not going to shy away from any of those particular intersections.

WR: Mmm yeah, thank you for that. I have one more question here and then I’ll turn it over to Claire. So along with the title, I was looking at how the book was structured into this triptych with three sections, one that seems like a youthful beginning, and then this sort of sexually-charged coming of age section, and then more of a contemplative end. I’m wondering if you could you explain more about the process of breaking the collection into three sections.

DP: You cut out bit, so let me see if I understood correctly. So basically, how did I come up with those three sections, how did I come into the structure while I was writing it?

WR: Yeah.

DP: So yeah, when I was writing the collection, I didn’t really think of any particular number of sections. All I knew was that at the very beginning, I had this kind of middle section of all of these sexuality-focused poems. That was actually the very first section for me to work on. So that was the first thing I was grappling with as a young, queer poet. Just my queer identity. What does it mean to be queer, to be a male-bodied person who loves other male-bodied people. And you know, the “Battle Born” state—a battle born for multiple reasons, not just for being Nevada. The tensions between a red and a blue state, the tensions with conservatism. Like, how does it feel to be a person who, you know, loves the cowboys but is more metropolitan themselves? So that was the first section I worked on, but then in my MFA, I started excavating the past more and so a lot of the first section’s poems came about.

That made me think, well I don’t want to have a collection of just two sections, and so I started writing more of a third section. That was the last section for me to work on, and that’s more of my voice now as a poet, I would say. And don’t get me wrong, my voice is always evolving, and I’m always growing as a poet. There’s no two same days in the poet’s life. My voice is constantly evolving. But my third section is probably where I’m closest to psychically speaking, and I think that you can probably see that too in the way that the collection progresses. Obviously, that youth to adulthood trajectory of it happens, but even in the way that tone exists across the poems, there’s a more mature sort of outlook in that final section. Not just because I wanted it to look that way in the book—I intentionally made it appear that way—but also the tone that I was just writing with in those last poems happened to be an older, wiser Dani.

It’s funny, because some of the poems that I wanted to put in the middle section, that deal with sex, ended up going in the last section at the request of my publisher. Specifically, my editor who’s super, super awesome. She was like, yeah the tone here is really representative of the third section, not the middle section, because there’s a lot of doubt and questioning happening in that second section that isn’t as prominent in the third section. Of course, there’s always questioning, there’s always unravelling, that happens throughout the entire book, throughout any liminal person’s identity, right? But in the third section, there’s definitely a more self-assured tone, and so I definitely put poems like “Conversion Boundary” in that last section. I wanted to put that in the middle because it’s definitely about romance, but it is more fitting to put in the last section. Same thing with “Dear Jeremy.” I wanted to put that in the second section, but it was more fitting to put it in the third section.

But I say all this with the caveat that I added poems to each section, towards the end to when I was revising the manuscript post-publication, or I guess post-acceptance by the press. I wanted to remove “Gates of Paradise” and I actually re-inserted it because my editors absolutely loved this poem, and I was like oh I didn’t think you guys would like this. I thought it represented, like, an older mindset about the speaker’s mom—which is actually my mom as the poet—and the sort of religious tension there which I personally moved past. I was like, well it’s not really representative, and she was like no it’s important because you’re providing this trajectory from this conservative background and how you’ve grappled with that and grown out of it. And sure, maybe you don’t relate to your mom the same way, maybe she doesn’t feel that way and you don’t feel that way anymore, but it’s important to represent that tension. And I was like, you know what, you guys are right. So I re-inserted that poem. Also, one of the final poems I added was “Texas Tango” in the middle section, and that was an experience I hadn’t written about but felt it was important to write about, so I wrote about it. And I’m really glad I did, because it provides a really good lead up to the final poems that happen in that last section with, you know, really intense affairs with older men and stuff like that. So the form has been this evolving process, but it started with the small germ of a slutty middle section, a sort of Bildungsroman of youth, sexual exploration, and then a later a self-assured coming into an identity.

Claire Carlson: Actually, I’m really glad that you were mentioning Nevada a little bit in your last answer, kind of grappling with the metropolitan and rural identities that are within that state. It is a very “Battle Born” state to live in and be from, and I noticed a lot of its influence in your poems, and I was wondering if you could just speak to what inspiration you’ve gotten from the desert, specifically Nevada, and what role it is playing in your artistic process and in this book?

DP: That’s a great question. And to give a more soulful answer, I feel like Nevada is always with me. I always have the desert sand in my lungs. I mean, this is kind of why I wrote the poem “150 Years of Molt.” It’s kind of an obscure title, but right around the time I wrote it was the 150th year of Nevada’s statehood, which is where that 150 comes from. So that’s like a fun fact but I don’t really tell anybody that. But yeah, that’s why I wrote that poem, because I feel so connected to Nevada’s complicated intention landscape. You know, the conservative, rural culture with the metropolitan areas of Reno and Las Vegas—which I adore of course. But then feeling like I’m somewhere in between, which is why I’ve always lived somewhere outside of Reno, having the relationship with the city but also enjoying that smaller, rural life. Being the more, dare I say, cultured person in the towns I exist in, right? I’m always like the queerest looking person, the most fashion-forward person.

I don’t know how big Missoula is, but it’s definitely like a college town and I imagine it’s a little bit smaller than some of the metropolitan areas. So I imagine it has some of that tension too. But yeah, with Nevada in my poetry, it’s always been something that I wanted to write about. And it’s funny too, because going to high school in Nevada, I was kind of ashamed of being a Nevadan, and I think a lot of people have this mindset when they come from a smaller area, or you know me, having moved way from California, what’s this small town I’m in. And you know, Reno isn’t even that big, but then when I got on to college, I started to reclaim more of my Nevadan identity. I realized I loved a lot of that imagery that was just kind of burned into my memory, and it started to come out organically. And that’s where my “Sanctuary” poem, which is the second poem in the collection, came about. I had this really intense memory of coming out to my best friend, who’s a lesbian. So we both kind of came out together, right? I remember we wanted to express this dual coming out, but also that being born within this random-ass thicket in the Nevada desert which was to me at the time a paradise, an oasis that I saw.

And also even with the town of Fallon, it’s called the oasis of Nevada, that’s kind of its tagline, so there’s this weird kind of paradise quality that exists within the Nevada desert that I really internalized, because I think there’s really no other state like it. It’s the driest state, but it’s also the most mountainous state. So you don’t only have the “more traditional desert” of Mojave, you have the high desert of Northern Nevada which I’m very familiar with, and you have all those mountains and you have Lake Tahoe, coniferous trees, different ecosystems. And you have a lot of riparian ecosystems too. I really like the fact that there’s this quasi-water-based environment, so even in Fallon there’s a lot of wetlands there and I really enjoy that. So there’s a lot of liminal ecological spaces in Nevada that marry well with my own personal liminal identity.

I’m always thinking about Nevada, I’m always writing about Nevada, I’m never going to stop, and with this collection, I wanted Nevada to be not only a central motif throughout the collection but kind of a central character itself. I can’t imagine having this collection be published without Nevada be so prominent in the way it is, because Nevada is in my soul always and I can’t ever detach myself from it. I’m currently physically in Oklahoma, but Nevada is always in my bio. I’m always there psychically, that’s kind of what I want to relay to people when I write my bio, because it’s always part of me. People say “home means Nevada”—I’m going to fuck up the tagline. But yeah, “home means Nevada” and I relate to that very deeply.

CC: Ugh, that makes me miss Nevada a lot. It is one of the most interesting states I’ve ever been to, and I’m probably very biased. I love that idea of these liminal ecological that you can find within the state. It’s an interesting one to think about because there’s so many different spaces in it. But yeah, sort of switching gears, this was a question I thought of in the beginning of our conversation as you were mentioning exploring popular culture in a lot of your writing, and that was also something I noticed in some of your poems. I know you mentioned Queer Eye in one of them, I don’t remember which one, talking about Darren Chriss, all of these influences. That’s something that I’ve always been really interested in incorporating in my own writing, and I’m curious how you’ve incorporated talking about popular culture, and maybe how that has also influenced your writing and whether it has inspired you or frustrated you. How do you incorporate popular culture into this as well?

DP: That’s a wonderful question, Claire. I think I’ve always had an eye towards popular culture, but my thinking and understanding of it has definitely evolved. I think that’s the more complex answer. Because one of the earliest poems in this collection is “Pearls,” which is the Mamma Mia masturbation poem. He literally was the first person I masturbated to, and it was because of that movie, and it was because I saw him as a gay man coming into his identity. I don’t know if you’ve seen Mamma Mia, but that was part of the film. And I really needed to write that poem because it was a milestone in my queer coming of age. I wrote that back in early 2015, like I had kind of internalized the advice of don’t necessarily write about pop culture, it will date your work. So I kind of like felt like I shouldn’t write about it. I mean, there is lots of bad advice you get. I wanted my poems to be indelible, or whatever shit I was trying to internalized back then.

But then as I grew older and started my MFA, I was like well fuck it, I’m just going to lead into my own voice, I’m going to write about the pop culture things that I want to write about, and so that’s where the poem that mentions Queer Eye came into play. That’s “They Call It LGBT Family Building.” And I just wanted to exploit the page of the poem to represent these cultural artifacts in a way, because they are so everyday and almost pedestrian, but they have a steep significance to me and to other people too. And so poetry was the way for me to really embrace that, but also I didn’t allow myself to embrace it until much later because of my own internalized shame about it.

You have not only “Pearls” but also the Queer Eye poem, you have my probably all-time favorite poem in this collection which was published in Camas, “Repping in the Borderlands.” That’s my favorite poem because it’s a marriage of pop culture and nonbinary identity. I never thought three years ago that I’d write about one of my favorite video game franchises and coming into my nonbinary identity. I never thought those two things would overlap. But lo and behold, this video game has a playable nonbinary character that I so deeply resonate with on many levels, and I’m so glad that my published was actually excited for me to add that poem because I added that poem post-acceptance. It just fit really naturally and organically in that final section, especially with a lot of the apocalyptic imagery that it’s surrounded by. So I’m really glad that I was able to write about a video game, because that was also another thing that I was told we can’t write about. And I was like, well I did this poem and this journal at the University of Montana published it and my publisher likes it, so I’m doing something right. But yeah, even the trope of the apocalypse is something that I’ve been thinking about. That’s very pop culture heavy too.

I’m very much into sci-fi shows—I was a Walking Dead fan, which is controversial because I think the latter seasons were the best. But you know, I was a Walking Dead fan in the day, I love shows like Wynonna Earp and Firefly. I don’t know if you’re familiar with these shows, but they’re kind of like sci-fi Westerns, I would say more specifically. They marry my love of the West with my love of sci-fi and geekdom, and I’m kind of thinking about that in terms of poetry. But I can’t imagine shying away from pop culture now. Like I said I recently wrote that Darren Chriss poem, it’s currently being considered by a journal that has a Glee—themed issue. I hope they accept it, because it’s like the perfect poem for that issue, and I’ve actually been rewatching Glee myself so Glee has been on my mind. And I wrote that Orville Peck poem like I said, and I’ve just been thinking a lot about how these pop culture influences aren’t only a part of my life, but how I can manipulate them and exploit them on the page and maybe in a formal way too. I know you guys haven’t seen the Orville Peck poem, but that’s a very very formal poem. It’s coming out in Foglifter next fall—I don’t know if you know about that journal, but it’s a San Francisco journal. I definitely exploited the caesuras and the unravelling of the page to represent kind of like the tensions of the queer cowboy that I was exploring in the poem. I mean, you guys know Orville Peck. He is a kind of phenomenon in itself, but I’m really drawn to that because I’m a phenomenon and I have this country west background but also I have all this queerness and so the Orville Peck poem was, not to belabor it, the perfect way to exploit that.

But yeah, pop culture is always on my mind. I look forward to writing more pop culture poems. I don’t know necessarily what they’re going to be, but they’re always there. I’ve also been writing about food too, which is kind of a pop culture thing. I’ve wrote about recently this biscuit in the Philippines called otap. I don’t know if you’ve ever had otap, but it’s basically your typical kind of biscuit but they have different—by biscuit I don’t mean like American southern, I mean like cookie biscuit, biscotti, twice baked that’s where the etymology comes from, harder cookie biscuit with sugar and everything. But they have different flavors like ube, and there’s a kind of mutant coconut in the Phillipines called buko pandan. Uko is the coconut but pandan is kind of like a leaf, like a foliage, that they use the flavor for things in the Philippines. And so they flavored it that way. And I mean, I don’t know where I’m going with that but I’ve written about otap, I’ve written about other foods in the Phillippines. There’s a dessert called halo halo that’s like this mixed dessert, it has like different beans and ice cream and evaporated milk. So those are other kind of pop cultural elements that I am incorporating into my poetry. So not necessarily like pop culture like the Walking Dead, but things that Filipinx people would know about, in that people have talked about and I talk to my friends about. So in that way, I feel like that’s it’s own sort of pop cultural thing. Sorry to go on tangents there, but I’ve been thinking about pop culture a lot.

CC: No worries, I love pop culture so it’s really interesting hearing your perspective on that. And also, with that poem I’m glad you mentioned “Repping in the Borderlands” because I know that Borderlands is a Gloria Anzaldúa book that is about that in-betweenness of being a Chicana woman and just exploring what it means to live in this other place. I feel like you have this intersection between this very scholarly, literary piece of work and then also talking about video games. It’s so interesting that you’re able to combine these many elements—I guess that’s not really a question, but what was your thought with incorporating Borderlands in the title? It’s a wonderful book, and I would love to hear your thoughts on it.

DP: Yeah, it’s great that you mentioned Anzaldúa’s La Frontera because that was something that was on my mind when I was writing that poem too. The title is kind of an exploitation of that as well. Like, having the article “the” before borderlands—even though borderlands is italicized and it’s a video game franchise—is kind of like these linguistic markers in the title itself that indicate some sort of subversion happening which just makes me feel really happy as a poet. It’s “Repping in the Borderlands,” borderlands as in the game and the space, you know? That was something I was really excited to exploit in that poem, but also thinking about the spaces that exist in the video game even though it’s intergalactic and it’s across all of these futuristic and almost utopian societies across space.

There is a lot of desert imagery too, especially in the main planet of Pandora in the video game. I don’t know if you’ve played the game or are familiar with it at all, but think Mad Max. That’s the main planet, very, very much. It’s that desert kind of hellscape that a lot of misfits have flocked to make it rich, which also really represents the Western mythology that a lot of us have grown up in. I don’t know if all of you are from the West, but that we all grew up in, right? That manifest destiny pneumatic was based around silver, California was based around gold—it all has to do with these people trying to strike it out on their own, they want to explore their independence, but they also want to in a capitalistic way get money. And I feel like that video game is a really perfect marrying of the Western mythology that I think about a lot and have written about, especially in my book. Obviously there’s the poem Western mythology, which is more about the myth of the safety of the West, and the fact that it’s actually a really cruel place.

Matthew Shepard’s murder was pretty much 20 years ago, it was in the 21st century basically. And so that was kind of like where that poem came from. But returning to the mythology of the Western ethos, borderlands is the perfect way to exploit that. In that game itself too, I’m so glad that we have video games like that being made because there’s so many intersections that exist there. Obviously, these video game creators are intentionally incorporating this apocalyptic stuff like Mad Max, they’re incorporating non-binary characters, and there are other queer characters in the game. And then it’s in this harsh desert landscape. It just so happens that a lot of privileged men were able to go out to the West back in the day because they had the wherewithal. Think about—what’s that one act where people were allowed to get parcels of land?

CC: Yeah, what is that? I know what you’re talking about.

DP: It’s on the tip of my tongue. But that was very, very much geared toward white men. For a long time, people of color, women, they couldn’t have this land out in the West. So it was very much a cis-het white man’s game, right? So it sucks that this Western mythology is based upon shitty white guys, when in fact I would say that the core of it is very, very queer. Outlaw itself is very, very queer, and that’s why I’m glad we have video games like Borderlands that are exploiting that. That’s why I can exploit that, and I have a tradition upon which I can build. That’s why I’m glad I have Orville Peck to look to as an inspiration. So yeah, that Borderlands poem is at the intersection of all these cool things that I’m very glad to be in right now as a 21st century queer Western poet.

CC: Thank you, that’s so awesome. Thank you for kind of giving us the behind-the-scenes of that poem. I’m really glad you were able to publish it. Winona, do you want to take the last few inspiration and poetry questions?

WR: Yeah totally. We had one more question which is kind of the cliché question, but I guess I’m curious what poets and artists have influenced your work and who are some of your favorites?

DP: For sure, no that’s a good question. It’s everything you know, I don’t think it’s too cliché because I have my own kind of catalog. I’ll start with some of the basics. Sylvia Plath, for sure. Her name is invoked in the collection itself. She was the first poet I read who I felt “got me.” I think every depressed teenager probably does that, but it was really important to me at the time. And she’s one of the few poets who I own every single one of her collections and I’ve read all of them voraciously. She really spearheaded my poetry career because I saw something in her confessions of mental illness that really resonated with me, that I hadn’t seen as a neurodivergent teenager myself. And so her bravery allowed me to be brave too, and that’s why I have poems like “OCD” in my collection. OCD has been really, really hard for me to write about, because I have such a weird individualized relationship. Her paving the way for that, it’s been really influential for me.

But kind of in a converse way, I don’t really think I write like these guys, but it was really important when I was first getting into poetry. The more spoken word slam poet Sarah Kay, and Neil Hilborn, as well as Andrea Gibson. I think all of them, or at least two of them, are affiliated with Button Poetry which is this big spoken word poetry organization that you may have seen YouTube videos for. They were really important for me in high school too, because I got to see that poetry was this living process, that people were reading, writing, performing poetry, and that was something that really enlivened the genre for me.

In high school, I actually competed in speech and debate. I was my team’s debate captain, and one of the events I did was poetry and prose interpretation. I would always read different slam poems, and I did very well. I would get first and second place, but that was my first kind of introduction to poetry as this performance but also as this living art that people still love and enjoy to this day.

Beyond that, people I’m closer to today as a practitioner and someone who speaks about craft, I’m thinking a lot about poets like Ocean Vuong, his semi-autobiographical book On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous is something that’s been really, really influential for me and the crafting of my own poetry. I think that just so happens not because he is very confessional and he takes a lot of associative leaps that I like to take in my own work, but his story reminds me a lot of my own. The tensions of being Asian-American and having people abroad, and also being this Asian-American queer person who’s attracted to maybe the rough and tough white man, you know. Maybe closeted and not coming into terms with your sexuality yet, that kind of tension is something that really resonates with me personally.

Other poets who I’ve been reading recently too. One of my friends actually, one of my dear friends—we went to the same MFA program—C.T. Salazar. His work really resonates with me because he explores spirituality and kind of an alternative look at Christian mythology in a very interesting and intriguing way. And he’s also nonbinary so we connect on that too, and he’s Latinx so we’re all these other intersections. So I identifying with him personally, and I can see kind of come out on the page.

I also want to shout out to folks like Jim Whiteside, he is one of my favorite living poets. I had the pleasure of reading with him in San Antonio at AWP last year. We read at this Louisiana, New Orleans style lounge and bar which I think is now closed, sadly, because of the pandemic. But we got to read together and I bonded with him over one of his poems about favorite gay porn stars, and we talked about that. I told him my favorite gay porn star, which I’ll name for you today because I have no shame. It’s Colby Keller. Which is really great, because he’s this lumberjack, this dirty blonde tall lumberjack man who’s also an artist. He has an MFA. So I feel like I really resonate with that story, his artistic-ness but also just the roughness that he brings. It’s funny because when I told Jim this, he was like “You really do have daddy issues, don’t you?” And I’m like, “Yep I do, you’re right.” But yeah, those are some of the voices in an endless catalog of people who inspire me.

WR: Yeah, I absolutely love Ocean Vuong. He’s been super influential for me too. And I think that’s really interesting talking about reading things aloud, because I think about how different writing is if it’s being read aloud versus written on the page. Like, when is something meant to be read aloud. Well, I think those are pretty much all the questions we have. Thank you so much for taking the time to do this, we greatly enjoyed it and are looking forward to having it up on the blog!

DP: Yeah, thank you for doing this and being so enthusiastic. It was so fun to see the whole Camas team, even Claire who’s sort of an emeritus. This was a joy, and I love talking about my work, especially with people from the West who, maybe selfishly, understand the imagery more. That’s always something that strikes me about people who read this book who are from Utah, or Colorado, or Arizona, or Nevada—they understand the imagery in a way that others maybe don’t. And maybe I’m making broad generalizations, but I always love it when I talk to people from the West about my book, because it’s such a love story for the West.